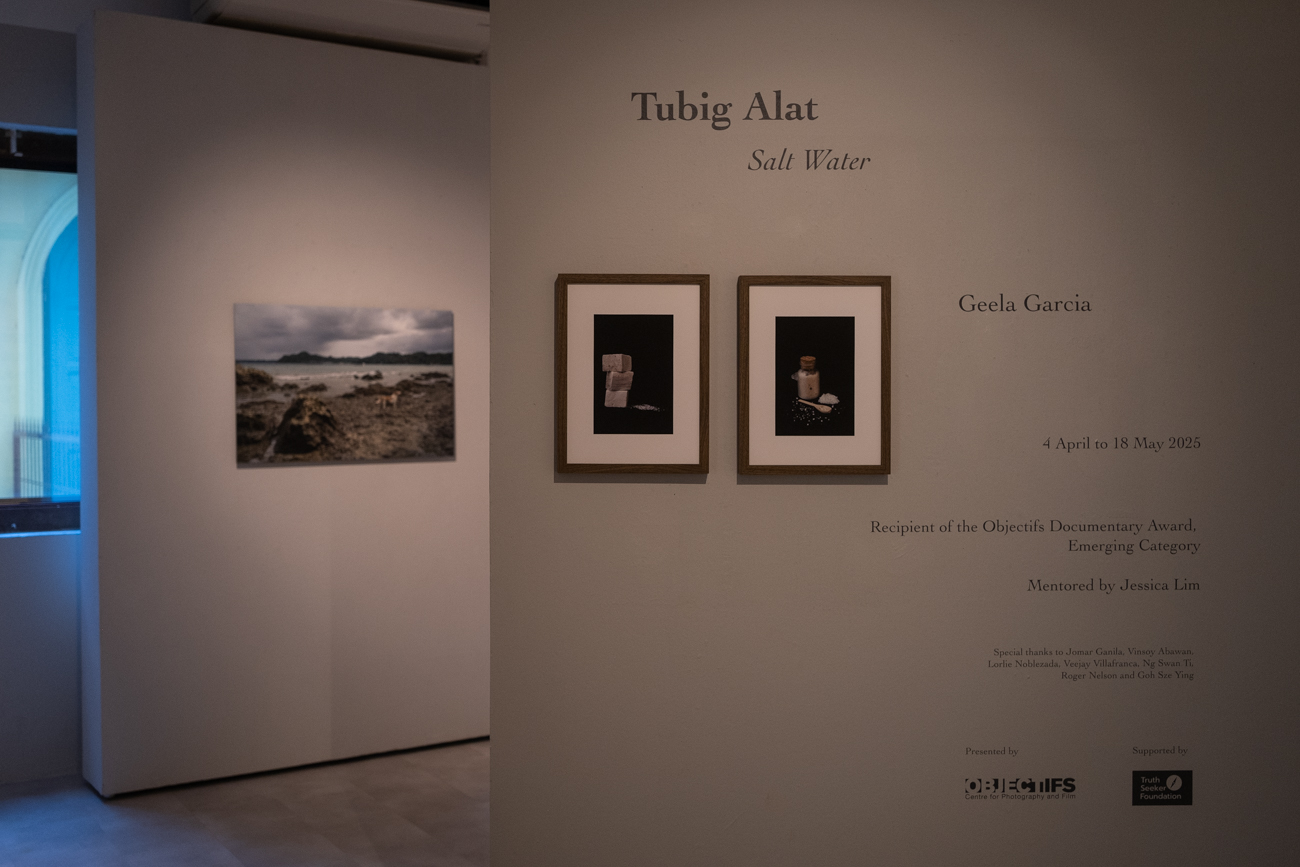

Tubig Alat (Salt water)

Guimaras and Iloilo2025

All life depends on salt.

Smoke blankets the room where Emma Ganila has been scooping brine into an assembly line of tin cans. As salt water boils and evaporates in the tins, blocks of white salt form. Emma has been making Tultul, an artisanal salt only found on Guimaras island.

On lloilo, an island right across Emma's, Lorie Noblezada watches her son, John, face strong breaking waves as he collects seawater with a bamboo pole to start the process of making Budbud salt.

Emma and Lorlie are some of the last artisanal saltmakers in the Philippines. Both have been safekeeping traditional saltmaking processes for decades. However, this craft is in fast decline.

Despite a long history of saltmaking, the Philippines, an archipelago with the fifth-longest coastline in the world, has not produced enough salt for its own needs for the past 15 years. The country has some of the rarest salts in the world, including Tultul and Budbud, and it only needs to utilise six percent of its coastline to be self-sufficient in salt. But local salts are on the brink of extinction due to unsupportive policies, industry neglect, and climate change.

The process of making artisanal salt is time-consuming and laborious, but still, Emma, at 74, spends her day inside the warm and smoky production house to cook blocks of Tultul salt; Lorie assesses the seasons and checks if the skies are clear to schedule production of Budbud salt. For these matriarchs, this craft, as much as it is a livelihood, is what binds their families' day-to-day living.

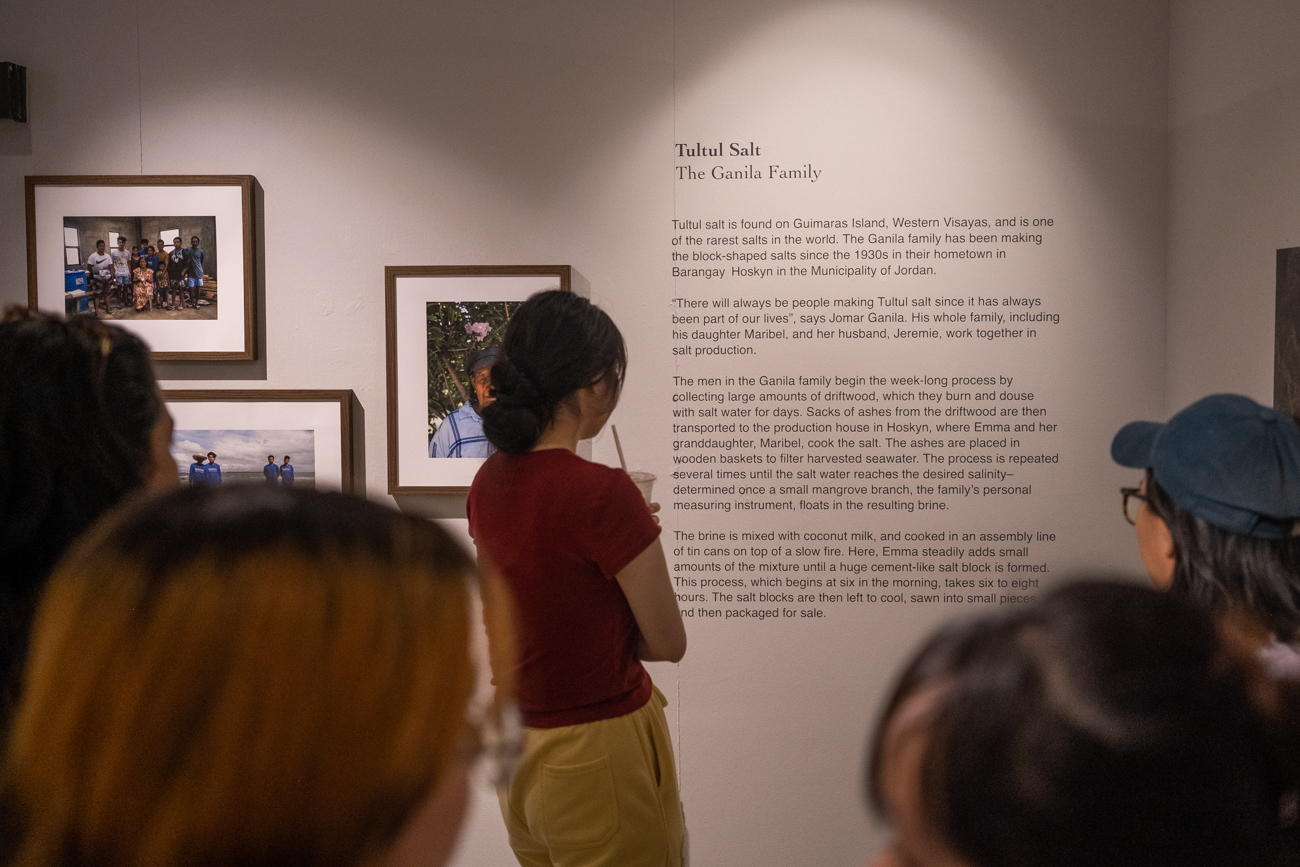

Tultul Salt

Tultul salt is found on Guimaras Island, Western Visayas, and is one of the rarest salts in the world. The Ganila family has been making the block-shaped salts since the 1930s in their hometown in Barangay Hoskyn in the Municipality of Jordan.

"There will always be people making Tultul salt since it has always been part of our lives", says Jomar Ganila. His whole family, including his daughter Maribel, and her husband, Jeremie, work together in salt production.

The men in the Ganila family begin the week-long process by collecting large amounts of driftwood, which they burn and douse with salt water for days. Sacks of ashes from the driftwood are then transported to the production house in Hoskyn, where Emma and her granddaughter, Maribel, cook the salt. The ashes are placed in wooden baskets to filter harvested seawater. The process is repeated several times until the salt water reaches the desired salinity- determined once a small mangrove branch, the family's personal measuring instrument, floats in the resulting brine.

The brine is mixed with coconut milk, and cooked in an assembly line of tin cans on top of a slow fire. Here, Emma steadily adds small amounts of the mixture until a huge cement-like salt block is formed. This process, which begins at six in the morning, takes six to eight hours. The salt blocks are then left to cool, sawn into small pieces, and then packaged for sale.

"There will always be people making Tultul salt since it has always been part of our lives", says Jomar Ganila. His whole family, including his daughter Maribel, and her husband, Jeremie, work together in salt production.

The men in the Ganila family begin the week-long process by collecting large amounts of driftwood, which they burn and douse with salt water for days. Sacks of ashes from the driftwood are then transported to the production house in Hoskyn, where Emma and her granddaughter, Maribel, cook the salt. The ashes are placed in wooden baskets to filter harvested seawater. The process is repeated several times until the salt water reaches the desired salinity- determined once a small mangrove branch, the family's personal measuring instrument, floats in the resulting brine.

The brine is mixed with coconut milk, and cooked in an assembly line of tin cans on top of a slow fire. Here, Emma steadily adds small amounts of the mixture until a huge cement-like salt block is formed. This process, which begins at six in the morning, takes six to eight hours. The salt blocks are then left to cool, sawn into small pieces, and then packaged for sale.

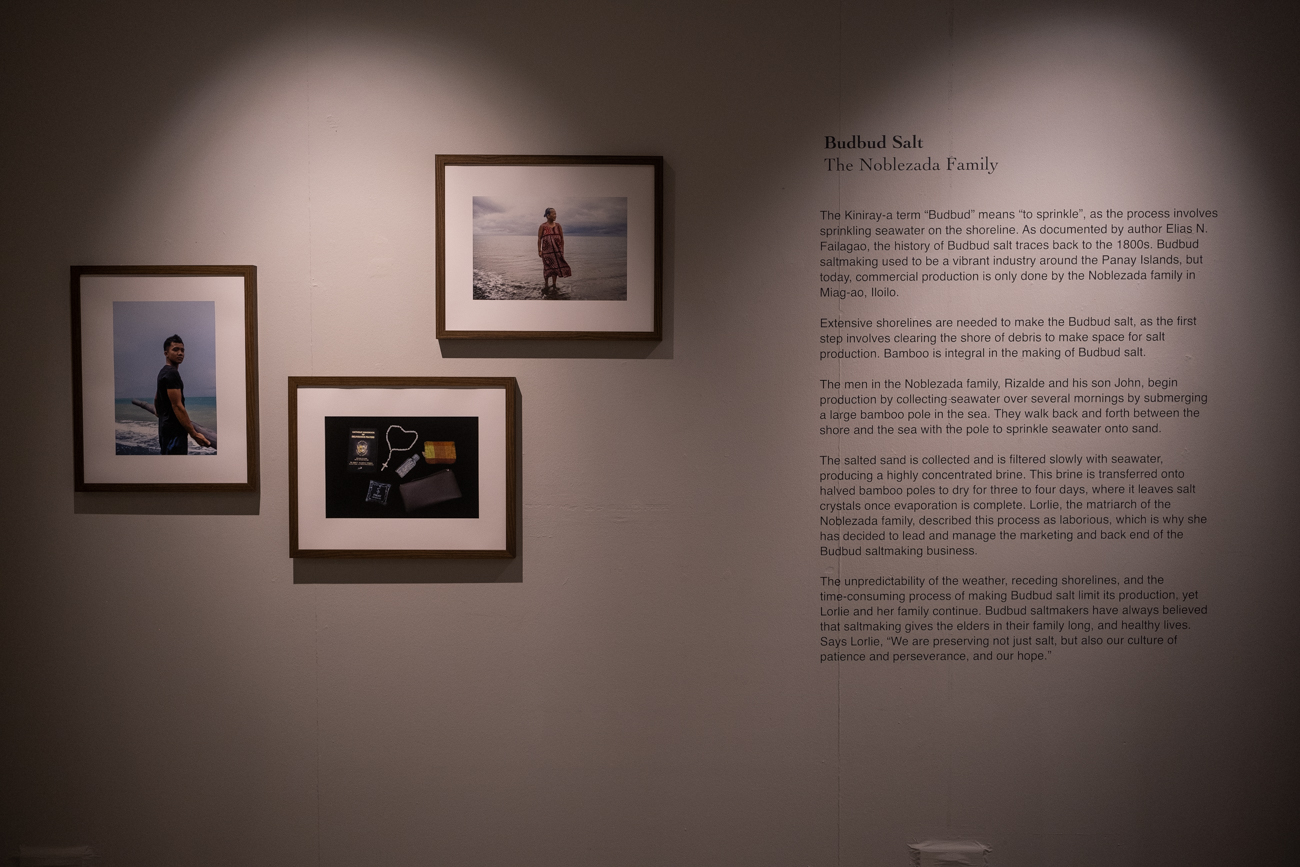

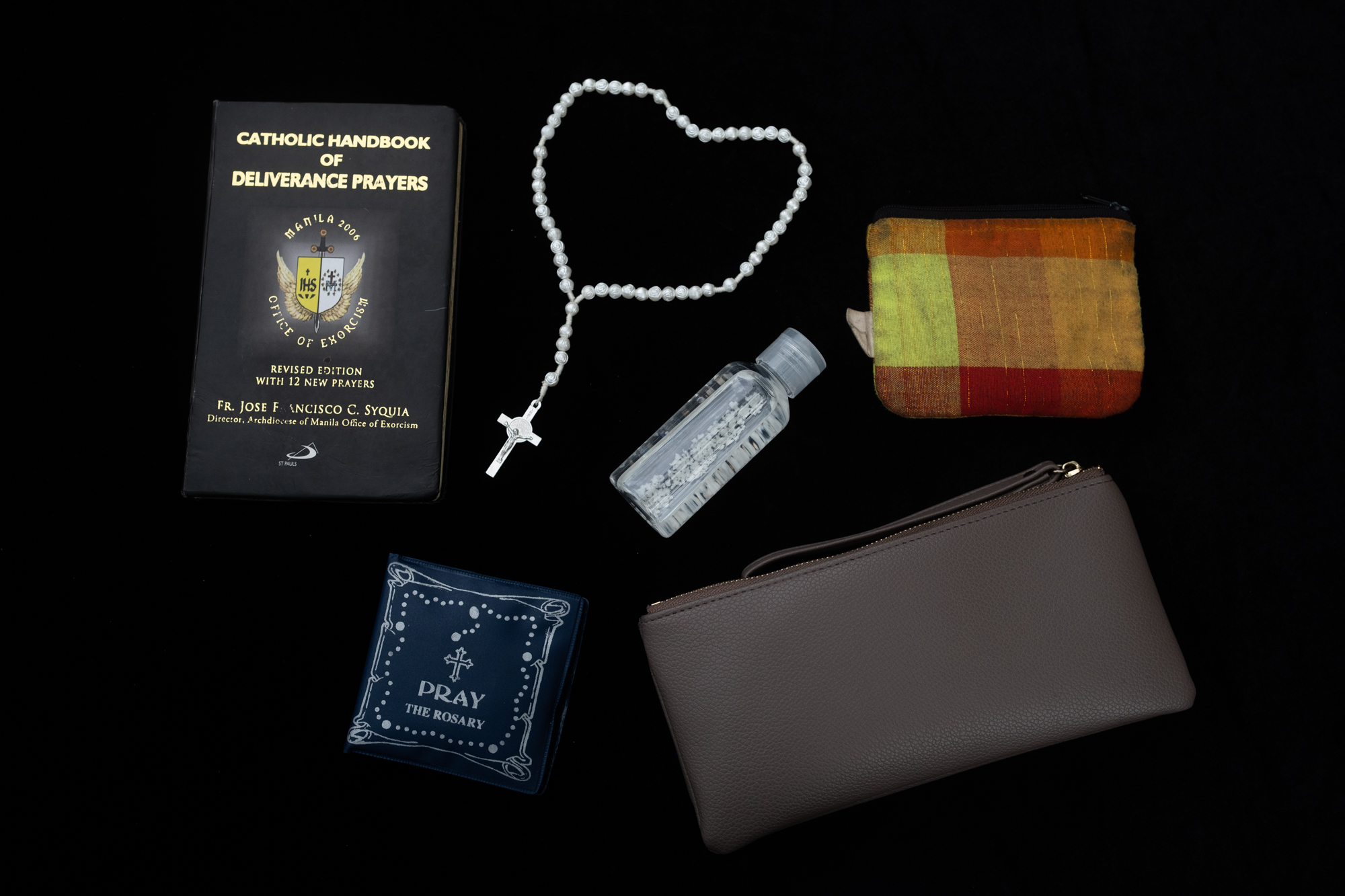

Budbud Salt

The Kiniray-a term "Budbud" means "to sprinkle", as the process involves sprinkling seawater on the shoreline. As documented by author Elias N. Failagao, the history of Budbud salt traces back to the 1800s. Budbud saltmaking used to be a vibrant industry around the Panay Islands, but today, commercial production is only done by the Noblezada family in Miag-ao, Iloilo.

Extensive shorelines are needed to make the Budbud salt, as the first step involves clearing the shore of debris to make space for salt production. Bamboo is integral in the making of Budbud salt.

The men in the Noblezada family, Rizalde and his son John, begin production by collecting -seawater over several mornings by submerging a large bamboo pole in the sea. They walk back and forth between the shore and the sea with the pole to sprinkle seawater onto sand.

The salted sand is collected and is filtered slowly with seawater, producing a highly concentrated brine. This brine is transferred onto halved bamboo poles to dry for three to four days, where it leaves salt crystals once evaporation is complete. Lorie, the matriarch of the Noblezada family, described this process as laborious, which is why she has decided to lead and manage the marketing and back end of the Budbud saltmaking business.

The unpredictability of the weather, receding shorelines, and the time-consuming process of making Budbud salt limit its production, yet Lorie and her family continue. Budbud saltmakers have always believed that saltmaking gives the elders in their family long, healthy lives.

Says Lorlie, "We are preserving not just salt, but also our culture of patience and perseverance, and our hope.

Photographs from the Objectifs Singapore exhibit April 4 - May 18, 2025